by Jared Strong, Iowa Capital Dispatch

March 27, 2024

A fertilizer spill this month in southwest Iowa killed nearly all the fish in a 60-mile stretch of river with an estimated death toll of more than 750,000, according to Iowa and... more

“To be radical is to simply grasp the root of the problem. And the root is us.” - Howard Zinn, 1999.

There’s a page on my website where I post the powerpoint slides from presentations I conduct. I took a look at that page this morning, and over the last five years I have conducted 69 programs for various groups, or about one a month on average. I reckon that at about half of these I get the question, “what can be done”, this in regard to Iowa water quality and pollution generated by the corn-soybean-CAFO (Confined Animal Feeding Operation) production model.

People have been thinking about “what can be done” for a long time.

People have been thinking about “what can be done” for a long time.

Because of industry and farmer recalcitrance and hostility toward regulation, various ideas for improving water quality have focused on either (1) enticing farmers to voluntarily adopt practices that reduce erosion and nutrient loss without major modifications to the production system or (2), promotion of concepts like increased crop diversity and improved soil health that do require substantial management changes.

I suppose you could also throw land retirement in there, but this has not been tried on any significant scale in Iowa since the 1980s.

The public has long been expected to be a financial participant in category (1) solutions, and Iowa’s nutrient reduction strategy is aligned with this cost-share concept. It’s also been apparent for a while now that momentum is building to ask the public to financially support category (2) solutions, and in fact this has already happened with public dollars used for cover crops, which are unharvested plants that help retain water and nutrients and enhance desirable soil qualities, thereby reducing water pollution.

This momentum seems to have gained steam since the election with the category (2) concept being repackaged (yet again) as regenerative agriculture. Regenerative agriculture focuses on building (or rebuilding) soil organic matter to improve water and nutrient cycling, reduce erosion, increase biodiversity, and sequester greenhouse gases. You can think of soil organic matter as the waste of live stuff and the remains of dead stuff, along with some fungi and other microscopic beasties that live in the soil. Various modern farming practices, especially tillage, tend to reduce organic matter and degrade that which remains.

The idea of regenerative agriculture in its several nomenclatures has been floated many times over the past 80-90 years or so, and has been embraced with varying degrees of seriousness. But the concept has never had widespread buoyancy in corn belt agriculture beyond a modest turn to port on tillage, that is, less mold-board plow (overturning the soil on top of itself) and more “conservation” tillage (disking and chiseling, primarily), something that was tugged along by conservation compliance in the 1985 Farm Bill. In Iowa, about 21% of the crop land is still in conventional tillage, 34% no-till, and 42% in reduced or “conservation” tillage (1). Tillage is seen by many farmers as more necessary for corn than soybean. Cover crops are used on about 4% of Iowa’s cropland, according the latest Iowa Nutrient Strategy progress report (2).

With the incoming Biden administration apparently serious about climate change, many in the NGO, foundation and academic world are excited about the prospect of the federal treasury’s barn door being flung open to help proselytize for regenerative agriculture. Born-again farmers would be paid to implement regenerative agriculture practices that will lay carbon to rest in their soils, instead of having it marauding around the atmosphere, melting polar ice caps and energizing super storms. And presumably this will improve water quality for the reasons stated earlier. This all is what we call “monetizing ecosystem services” in the biz, because apparently the intrinsic value of healthy soil, reduced erosion, and cleaner water is so low to the farmer that they won’t do it unless we pay them to do it.

Now permit me to say now that I am all for regenerative agriculture and I have stated so in this space, albeit without using the specific term. But there is a whiff of something moldy hovering over this. Even the optimists know these types of approaches will likely take generations to deliver the water quality we want. But, I can tell you there is a feeling of futility about Iowa water quality—4% of the land in cover crops after eight years of the Iowa Nutrient Reduction Strategy is a kick in the crotch, let’s just be honest. So, we’re going to give mouth-to-mouth to the constipated Soil Health movement of the last decade and rebrand the resulting Lazarus as Regenerative Agriculture. It’ll probably be worth at least another 4-8 years of relevance for a lot folks, relevance being the real long-term goal here and one of the reasons our water still stinks.

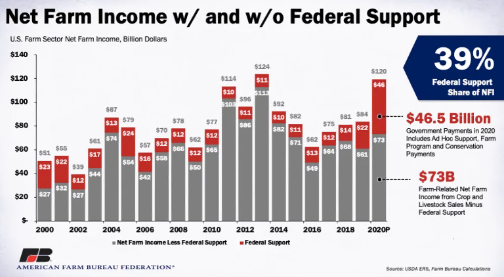

Again, to emphasize – I’m down with regenerative agriculture or whatever fancy ornamental names you want to hang on this tree. But for crying out loud, shouldn’t we be asking agriculture to perform at some baseline level of environmental performance before brainstorming yet another unaccountable way to funnel your money to them for uncertain outcomes? These are folks that brag about the size of their bulging federal largesse while the rest of the country tries to recover from the worst crisis in a century (see below). The public has been asked to invest over and over and over again in this production system; isn’t it about time we had a say in how it is operated?

There are things we can do now that would improve water quality now. But many of us need to could quit worrying about our relevance for five minutes and have the courage to state the obvious.

What follows is the answer I give when asked “What Can Be Done.” At least three of the five points I make are universally acknowledged throughout the industry to be bad practices. All five of them are things that allow the existing production system to remain largely intact, with or without soil health, regenerative agriculture, or whatever you want to call it. The reason we don’t do these things isn’t because they won’t work, it’s because there are a lot of cowards when it comes to Iowa water quality.

Ban row crop agriculture in the 2-year flood plain.

We plant 276,000 acres where inputs like fertilizer and pesticides are washed away into the stream network and the Gulf of Mexico every other year (3). This is an area of land that exceeds the combined area of all our state parks. This is perverse. Why are we doing this?

Ban fall tillage.

Universally recognized as a practice with disproportionately bad environmental effects, people at Iowa State University have been discouraging it for decades. It’s especially bad following a soybean crop. Increases soil erosion (keep your eye open for “snirt” this winter), increases nutrient loss, increases greenhouse gas losses from farmed fields. I get that if a farmer likes tillage and wants to farm a lot of acres, he/she might feel pressed for time in the spring to get it all plowed. And if you spend your winters in Ft. Myers or Scottsdale, it might be nice to have the plowing done so you have time to get the RV cleaned up for Northern Minnesota in July. Not my problem. It’s polluting our water, it’s not necessary for growing corn and soybeans in Iowa and it’s ridiculous that we still allow this. Side story: Several years ago, I was talking about this in a meeting and farmer angrily pounded his fist on the table and said: “You know why we do fall tillage? Because we have to!” Ok. I would have liked to have said, “You know why I tolerate bad water? Because I have to!”

Ban manure on snow and frozen ground.

Again, pretty much universally acknowledged as a sub-optimal practice, if not down right stupid. And in the case of manure on snow, clearly destructive of water quality. Yes, we already have some rules about this in Iowa, but they are so riddled with loopholes that they are practically meaningless. Example: if there is snow on the ground on March 1, it’s pretty easy to find some with manure on it. Great for smelly snowball fights, really bad for our rivers. I get that the manure pit may fill up faster than expected; again, not my problem. Build a bigger pit!

Make farmers adhere to Iowa State University fertilization guidelines.

What’s the point of ISU having a Nitrogen fertilizer rate calculator if nobody is going to follow it? Despite what you might hear from the ag advocacy organizations, farmers do over apply fertilizer. It’s endemic to Iowa’s production system. Also, newsflash: Nitrogen IS cheap; in fact, it’s hardly ever been cheaper than it is now. If I’ve said it once I will say it a thousand times: how do we give farmers license to do whatever they want with inputs and then ask the taxpayer to mitigate the pollution? It’s insanity.

Reformulate CAFO regulations.

Let’s face it, Iowa’s Master Matrix regulatory framework for livestock operations is like a zip tie handcuff on King Kong. It enables farmers to apply manure nutrients beyond crop needs, and it provides for no management of nutrient inputs at the watershed scale, sentencing many rivers to a polluted oblivion. We cannot continue to wantonly cram hogs into Iowa and meet the objectives of the nutrient strategy, at least not without effectively regulating nutrient inputs. And believe me, I am far from the only person that knows this. The fact that this continues to go unacknowledged by our politicians, the industry, and many of the state’s institutions is nothing short of sinister.

Well, there you have it. Nothing on that list should cost you, the taxpayer, a dime. But I will tell you, if you want clean water, you will have to demand it.

Originally published on Chris Jones blog on water quality and agriculture Dec. 16, 2020

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Footnotes:

Howard Zinn, 1922-2010

If you don’t know, Howard Zinn (quote at the beginning) managed to write at once what might be the most admired and the most hated book about America (the latter almost certainly is true): A People’s History of the United States. If Zinn was right, true change in America comes from below and progress only happens when people resist and organize. If you’re waiting for the water quality elites here in Iowa (and you can put me in that group if you want to) to solve the water quality problem, you’re going to wait a while. Sorry. The industry will pollute your water for as long and to the degree that you let it.

1 - Agriculture census shows more conservation acres in Iowa. https://www.kcrg.com/content/news/Agriculture-census-shows-more-conserva....

2 - Iowa Nutrient Reduction Strategy 2018-19 Annual Progress Report. https://store.extension.iastate.edu/Product/15915.

3 - Personal Communication, Calvin Wolter, Iowa DNR, December 8, 2020.

Chris Jones, IIHR Research Engineer

Water Quality Monitoring & Research

IIHR — Hydroscience & EngineeringCollege of Engineering

You can sign up for Chris' blog on water quality and agriculture at: https://www.iihr.uiowa.edu/cjones/welcome/

++++++++++++++++++++++

by Jared Strong, Iowa Capital Dispatch

March 27, 2024

A fertilizer spill this month in southwest Iowa killed nearly all the fish in a 60-mile stretch of river with an estimated death toll of more than 750,000, according to Iowa and... more

by Robin Opsahl, Iowa Capital Dispatch

March 25, 2024

The Iowa Senate on Monday sent a bill to the governor’s desk restricting stormwater and topsoil regulations, a measure Democrats say unfairly limits local control.

The Senate... more

Iowa Capital Dispatch

March 11, 2024

The Iowa House passed legislation Monday on local storm water and top soil regulation after the same bill failed last week.

... more

An India online media company, Quint Digital Limited of Delhi, has purchased a 10 percent stake in Lee Enterprises, Inc., owner of the Quad City Times, the Dispatch/Argus and more than 70 other media properties.

Quint Digital and three of its owners, Raghav Bahl, Ritu Kapur and Vidar Bahl... more

Powered by Drupal | Skifi theme by Worthapost | Customized by GAH, Inc.