by Keith Schneider | The New Lede, Iowa Capital Dispatch

April 21, 2024

VENICE, Louisiana — Kindra Arnesen is a 46-year-old commercial fishing boat operator who has spent most of her life among the pelicans and bayous of southern... more

You wouldn't know it listening to Iowa agricultural industry groups or state ag department officials, but a new report from University of Iowa researchers makes it clear: state farm operators are doing a lousy job of keeping nitrogen fertilizer out of the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers.

How bad a job are ag businesses doing in preventing nitrates-nitrogen from seeping from their farm field drain tiles into state waterways?

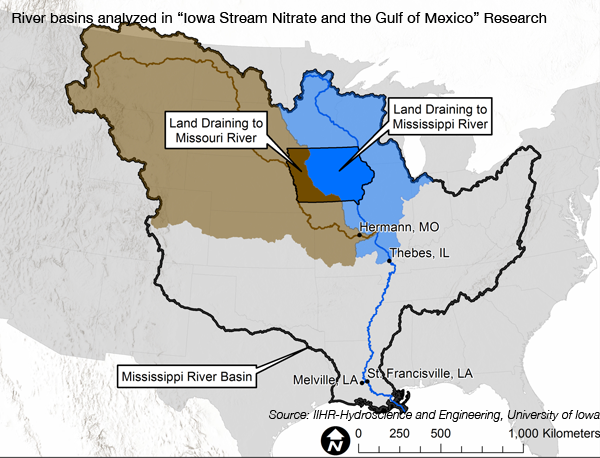

In the Upper Mississippi River Basin, Iowa contributes 21 percent of the water, comprises 21 percent of the land area, but is responsible for nearly half (45 percent) of nitrate-nitrogen pollution that flows into the Mississippi River.

In the Missouri River Basin, Iowa contributes 12 percent of the water, comprises only 3.3 percent of the watershed land area, yet is responsible for more than half (55 percent) of the nitrate-nitrogen polluting the Missouri River.

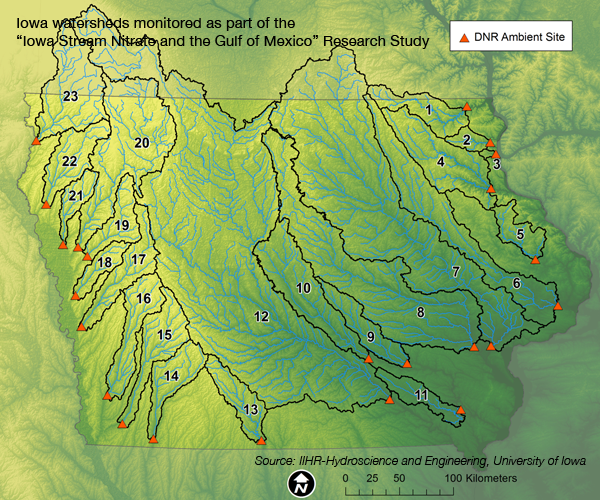

Those are two of the key findings of a peer-reviewed study entitled "Iowa Stream Nitrate and the Gulf of Mexico" published April 12 by researchers using data drawn from monitors on 23 Iowa watersheds, 12 draining into the Mississippi River and 11 into the Missouri River. CLICK HERE to view the full scientific report by IIHR — Hydroscience & Engineering at the University of Iowa and the Iowa Geological Survey.

Industry groups like the Iowa Corn Growers and Iowa Soybean Association along with the Iowa Department of Agriculture and Land Stewardship (IDALS) have promoted a narrative that voluntary measures by farmers are having an impact on lowering nitrogen pollution of state waterways.

But the new study of nitrate-nitrogen runoff from 1999 through 2016, points out other states in the Upper Mississippi and Missouri River watersheds "seem to be stable or increasing at a slower rate than the Iowa-inclusive area. . ."

In other words, other states in the Mississippi and Missouri watersheds are doing a much better job than Iowa in controlling nitrate-nitrogen pollution.

Because of Iowa's outsized contribution to nitrogen runoff, the reports notes: "An opportunity exists for land managers, policy makers and conservationists to manifest a positive effect on water quality by targeting and implementing nitrate reducing practices in areas like Iowa while avoiding areas that are less likely to affect Gulf of Mexico hypoxia."

In short, if you want to reduce the so-called "dead zone" in the Gulf of Mexico from oxygen-depleting nitrate-nitrogen pollution, a great place to focus those efforts would be Iowa farmland.

"Since 1999, nitrate loads in the Iowa-inclusive basins have increased and these increases do not appear to be driven by changes in discharge and cropping intensity unique to Iowa," the report states. "The 5-year running annual average of Iowa nitrate loading has been above the 2003 level for 10 consecutive years, implying that Gulf hypoxic areal goals, also based on a 5-year running annual average, will be very difficult to achieve if nitrate retention cannot be improved in Iowa."

The study findings undermine claims by ag industry groups and state ag officials that significant progress is being made to lower nitrate-nitrogen run-off through voluntary conservation practices funded by farm operators, ag industry groups and the state/federal government programs.

Other key findings of the report:

• "We are not aware of other detailed estimates of Iowa’s nitrate-nitrogen load to the Missouri River Basin and Upper Mississippi River Basin. It’s clear that Iowa is a major contributor to both, especially the Missouri River Basin. In some years, the Missouri River would have nearly no nitrate-nitrogen without contributions from Iowa (e.g. 2003, 2006, 2011)."

• "To our knowledge, however, how western Iowa streams draining only 3 percent of the Missouri Basin can dominate overall Missouri River nitrate-nitrogen loading has not been previously reported in any published literature. This illustrates the importance of implementing nitrate-nitrogen mitigation strategies that address not only the level, tile-drained landscapes in northern and eastern Iowa but also the hillier terrain of western Iowa where constructed drainage is less common."

• "Approximately 90 percent of the state’s stream nitrate-nitrogen can be sourced to the 72 percent of the state’s land area that is in crop cultivation. Previous research in Iowa has shown that a watershed’s nitrate-nitrogen load is directly linked to the area portion cultivated for corn and soybeans. This intense production of carbohydrates and protein has resulted in the state being a leading contributor to Mississippi and Atchafalaya River Basin nitrate-nitrogen loads and Gulf hypoxia."

The 2017 Iowa Nutrient Reduction Strategy (NRS) Annual Progress report issued last December by Iowa ag department officials even claims insufficient data to address the nitrogen runoff problems. "Data availability to accurately assess progress in each category of the logic model is a primary hurdle," the NRS report stated. And, despite more than seven years to address the issue, the state ag department report states "a sufficient period of record is also needed to evaluate progress."

The Iowa Agriculture Water Alliance – an industry lobby/public relation organization funded by the Iowa Soybean Association, Iowa Corn Growers and Iowa Pork Producers Association – recently issued a glowing newspaper opinion article proclaiming "despite the amazing progress of the past five years, the best is yet to come."

"Across Iowa, we are seeing great progress in (sic) when critical factors come together: a watershed plan, financial assistance, technical assistance, and engaged agribusiness, community members, and farm-leaders," the water alliance executive director Sean McMahon wrote in the op-ed article.

Data from the new university scientific report, however, indicates conservation measures to reduce overall nitrate-nitrogen runoff into the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers have largely been ineffective in stemming pollution of Iowa waterways by fertilizers used to grow corn and soybeans.

Planting cover crops – touted as the leading practice to curb nitrogen runoff from water released through field tiles into state waterways – totaled just 302,000 acres in 2016 and resulted in a reduction of nitrogen runoff of 1,375 tons, or .002 percent of the 525,654 tons of nitrogen released into Iowa streams in 2016, according to the 2017 NRS Progress report.

Even using the optimistic assumption Iowa farmers planted an additional 300,000 acres of cover crops with their own money, the 600,000 total acres still represents only a small fraction of 1 percent of the 26.6 million acres of corn, soybeans and other annual and perennial crop land in the state.

Ag industry groups also like to state that more than $400 million is being spent "to address water quality challenges," as McMahon did in the water alliance article printed in the Cedar Rapids Gazette May 30.

But more than 90 percent of that $420 million is actually federal "base programs" including CRP (Conservation Reserve Program) money paid state farmers not to plant crops on marginal land.

The CRP program has been around since 1956 (originally called the Soil Bank Program) with the purpose of reducing land erosion, improving water quality and providing wildlife habitat.

"It is vital to note that most public funding comes from sources that could be considered base programs," the NRS report states. "These programs fund conservation efforts that were in public use for many years before the nutrient reduction strategy was initiated."

The new law signed by Gov. Reynolds in January would provide a total of $270 million over 11 years to fund water quality improvements, but critics say that amount is inadequate and the legislation provides no requirement to measure the program's effectiveness.

Only $4 million will be provided for water quality work in this fiscal year and $8 million next year. Starting in 2020, an estimated $27 million to $30 million would be available each year until 2029, under the legislation.

CLICK HERE to download the full Annual Progress Report of the Iowa Nutrient Reduction Strategy.

by Keith Schneider | The New Lede, Iowa Capital Dispatch

April 21, 2024

VENICE, Louisiana — Kindra Arnesen is a 46-year-old commercial fishing boat operator who has spent most of her life among the pelicans and bayous of southern... more

by Jared Strong, Iowa Capital Dispatch

March 27, 2024

A fertilizer spill this month in southwest Iowa killed nearly all the fish in a 60-mile stretch of river with an estimated death toll of more than 750,000, according to Iowa and... more

by Robin Opsahl, Iowa Capital Dispatch

March 25, 2024

The Iowa Senate on Monday sent a bill to the governor’s desk restricting stormwater and topsoil regulations, a measure Democrats say unfairly limits local control.

The Senate... more

Iowa Capital Dispatch

March 11, 2024

The Iowa House passed legislation Monday on local storm water and top soil regulation after the same bill failed last week.

... more

Powered by Drupal | Skifi theme by Worthapost | Customized by GAH, Inc.